Sciam, Kouki, & Seta

It doesn’t appear out of place to find Syrian stores and cafés in the old quarters of Rome; a meeting point between East and West in two of the oldest inhabited cities of the world: Rome (aka Caput Mundi) and Damascus (aka 'Pearl of the East'). With the migration of skilled Syrians, Rome welcomed them with open arms in the 1980s to fill a void in the rug industry. Damascenes brought with them the knowledge and techniques of Caucasi (Caucasian) and Tabrizi (Tabriz) rugs, considered to be the most praised in the Middle East. A time of economic boom for Italy, the decorative hand-made floor coverings were in high demand. Rather than invading the market and competing with local artisans, the foreigners provided an unavailable and highly requested competency in distinguishing, repairing, and cleaning of the prized interior luxuries.

It doesn’t appear out of place to find Syrian stores and cafés in the old quarters of Rome; a meeting point between East and West in two of the oldest inhabited cities of the world: Rome (aka Caput Mundi) and Damascus (aka 'Pearl of the East'). With the migration of skilled Syrians, Rome welcomed them with open arms in the 1980s to fill a void in the rug industry. Damascenes brought with them the knowledge and techniques of Caucasi (Caucasian) and Tabrizi (Tabriz) rugs, considered to be the most praised in the Middle East. A time of economic boom for Italy, the decorative hand-made floor coverings were in high demand. Rather than invading the market and competing with local artisans, the foreigners provided an unavailable and highly requested competency in distinguishing, repairing, and cleaning of the prized interior luxuries.

Youssef Hallak, a local of Damascus who sold rugs to foreigners in Bab Sharki, is one of the first representative of such individuals. Arriving in 1980, Hallak offered his services to individuals until the opening of his own independent workshop Sciam (pronounced 'Sham') in the artisan district of Rome, in the heart of the old city. Specialized in Eastern rugs, Hallak relied heavily on his Syrian connections. To manage the demand, artisans from Damascus’ Souq al Arwan, named after Byzantine traders, were employed in his bottega on Via del Pelligrino. In fact, these artisans, namely Ziyad Kouki and Samer Hareb, expanded the Damascene tradition to other stores, workshops, and cafés in the old quarter.

Youssef Hallak, a local of Damascus who sold rugs to foreigners in Bab Sharki, is one of the first representative of such individuals. Arriving in 1980, Hallak offered his services to individuals until the opening of his own independent workshop Sciam (pronounced 'Sham') in the artisan district of Rome, in the heart of the old city. Specialized in Eastern rugs, Hallak relied heavily on his Syrian connections. To manage the demand, artisans from Damascus’ Souq al Arwan, named after Byzantine traders, were employed in his bottega on Via del Pelligrino. In fact, these artisans, namely Ziyad Kouki and Samer Hareb, expanded the Damascene tradition to other stores, workshops, and cafés in the old quarter.

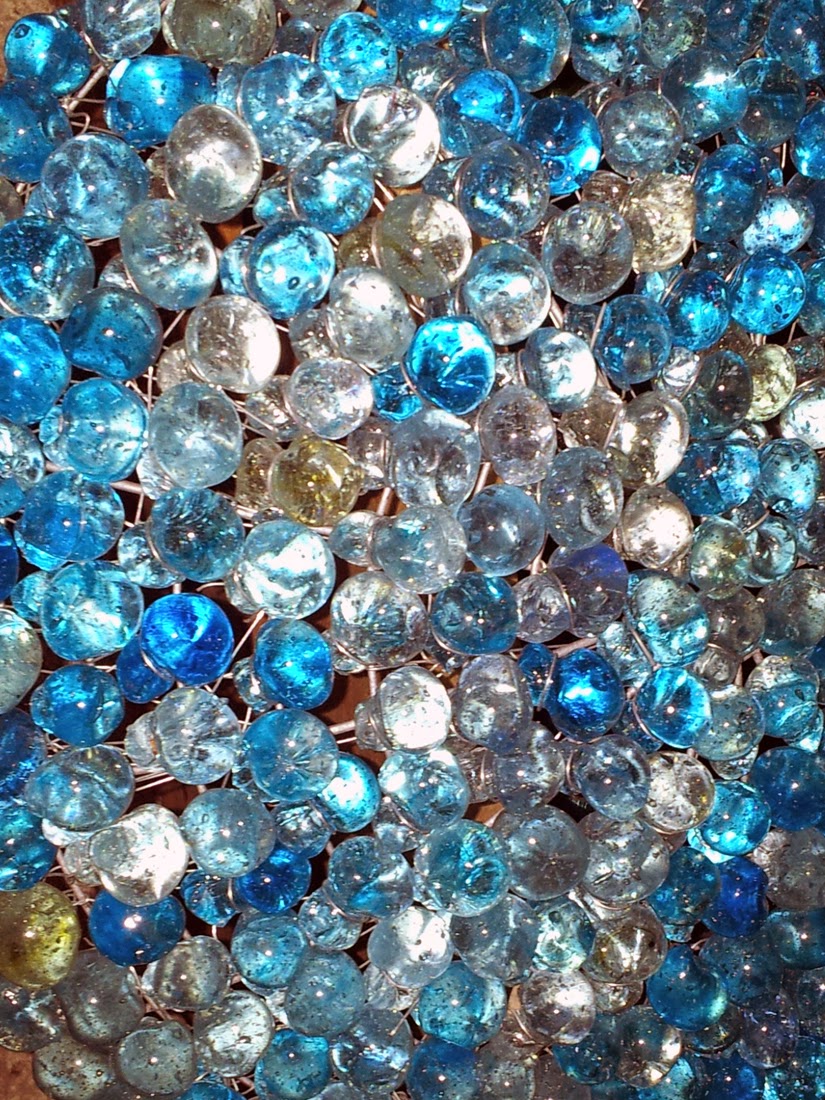

With the decline in demand of Caucasi and Tabrizi rugs, Hallak found other ways to bring Syrian handicrafts into the local market by introducing hand-blown glassware from one of the oldest factories right outside the old city walls of Damascus. The slowly rising success encouraged the importation of more glass objects, including light fixtures, sculptures, dishes and vases. Though Italy is itself recognized for its glass making skills, glass-blowing was discovered along the coast of the Mediterranean, in current day Syria, towards the end of the 1st Century BC. In fact, the invention revolutionized the production of glass at the time. Due to its fast and easy process, the products became readily available to the common person for the first time in history. In Syria today, only a few skills glass blowing factories remain. The ancient and traditional art form, a skill handed down from generation to generation, is at risk of being forever destroyed. The appreciation for such objects reached its peak in Rome in 2003. Though the local market seems to have fallen into disinterest, the foreign tourists still show an interest.

With the decline in demand of Caucasi and Tabrizi rugs, Hallak found other ways to bring Syrian handicrafts into the local market by introducing hand-blown glassware from one of the oldest factories right outside the old city walls of Damascus. The slowly rising success encouraged the importation of more glass objects, including light fixtures, sculptures, dishes and vases. Though Italy is itself recognized for its glass making skills, glass-blowing was discovered along the coast of the Mediterranean, in current day Syria, towards the end of the 1st Century BC. In fact, the invention revolutionized the production of glass at the time. Due to its fast and easy process, the products became readily available to the common person for the first time in history. In Syria today, only a few skills glass blowing factories remain. The ancient and traditional art form, a skill handed down from generation to generation, is at risk of being forever destroyed. The appreciation for such objects reached its peak in Rome in 2003. Though the local market seems to have fallen into disinterest, the foreign tourists still show an interest.

After Hallak’s success at opening a restaurant in Old Damascus called Zeituneh, along one of the main streets of the old city called Medhat Bacha towards one of the eight gates of the old city, the eastern gate in the Christian quarter called Bab Sharki; in 2000 he opened up Sciam Café. Taking the place of the rug repair and cleaning area of his store, the interiors were transformed into a Damascene interior with imported wood beam ceilings decorated in the hand-painted ajami technique, hand-blown glass fixtures, hand-sewn Oriental tapestries, and hand-carved wood tables and chairs. The café became an automatic hit among locals and tourists with a continuous demand for typical Syrian teas and flavoured argilehs (hooka).

After Hallak’s success at opening a restaurant in Old Damascus called Zeituneh, along one of the main streets of the old city called Medhat Bacha towards one of the eight gates of the old city, the eastern gate in the Christian quarter called Bab Sharki; in 2000 he opened up Sciam Café. Taking the place of the rug repair and cleaning area of his store, the interiors were transformed into a Damascene interior with imported wood beam ceilings decorated in the hand-painted ajami technique, hand-blown glass fixtures, hand-sewn Oriental tapestries, and hand-carved wood tables and chairs. The café became an automatic hit among locals and tourists with a continuous demand for typical Syrian teas and flavoured argilehs (hooka). Ziyad Kouki and Samer Hareb, two craftsmen who had their own practice in Souq Al Arwan, like Hallak, came with the skills and will to work hard and independently succeed. The Syrian community in Rome, and Italy as a whole, is quit small; which essentially meant that those who came had to make it on their own with their owns savings and initiatives. Kouki and Hareb demonstrate the Damascene survival method of continuously assessing the local market and adjusting accordingly. With optimism and Syrian charisma of a chatty salesmen; always willing to find whatever words to communicate with customers, whether in German, English, Italian, French or Arabic, they have evolved since their arrival to Rome in the late-1980s.

Ziyad Kouki and Samer Hareb, two craftsmen who had their own practice in Souq Al Arwan, like Hallak, came with the skills and will to work hard and independently succeed. The Syrian community in Rome, and Italy as a whole, is quit small; which essentially meant that those who came had to make it on their own with their owns savings and initiatives. Kouki and Hareb demonstrate the Damascene survival method of continuously assessing the local market and adjusting accordingly. With optimism and Syrian charisma of a chatty salesmen; always willing to find whatever words to communicate with customers, whether in German, English, Italian, French or Arabic, they have evolved since their arrival to Rome in the late-1980s.

Kouki left Sciam workshop and opened independent activity (Via Dei Coronari 213) selling, repairing, and cleaning valuable old rugs in the famous Via dei Coronari, renown for its famous antiquariati. Around nine years ago, Mohammad Lutfi joined Kouki's rug repair workshop, in order to continue to provide Eastern skills deriving from Damascus' Souq al Arwan. Like Hallak's willingness to adjust and alternate, Kouki expanded his shop across the street to also sell Syrian and

Kouki left Sciam workshop and opened independent activity (Via Dei Coronari 213) selling, repairing, and cleaning valuable old rugs in the famous Via dei Coronari, renown for its famous antiquariati. Around nine years ago, Mohammad Lutfi joined Kouki's rug repair workshop, in order to continue to provide Eastern skills deriving from Damascus' Souq al Arwan. Like Hallak's willingness to adjust and alternate, Kouki expanded his shop across the street to also sell Syrian and

Egyptian hand-blown glassware in a store called, as the first, Kouki. On the same street, only 20 meters away, his daughter Leila also opened a store, appropriately called Leila's (Via dei Coronari 224), that sells, diversely from her father, Murano glass accessories from cute beaded earrings to up-scale jewellery. As the importation of Syrian objects is diminishing, the now rug-man turned local merchant evaluated the European economy and included to his products Turkish Iznik tiles and Murano glass objects, mixing East and West in the once exclusive Caucasi-Tabrizi occupation.

Samer Hareb essentially took the same path as Kouki, beginning in Hallak's workshop and going independent. In 2000 he opened his own rug shop, which also sold glassware through the collaboration with his brother living in Damascus, in the artisan street of Via Panico. In the summer of 2014, effectively altering in direction, Hareb opened Via della Seta on Via dei Coronari. From the decoration, the café speaks Old Damascus. In fact, every detail is a reminder of Hareb’s past. Being a proud Damascene from Bab Al Jabeih, Hareb does not leave a moment to remind passer-bys that he is from the oldest inhabited city in the world and personally makes everything on his menu alla Damascena. With the exception of the hand-made kibbeh from a Syrian woman’s kitchen, Hareb wakes up every morning to make his menu ‘fresh’. The quality and distinction of Via della Seta is that the Damascus cuisine is authentically prepared by a Shami, a rare match in itself. Even in Damascus a Damascene is rare, so finding one in Rome cooking food is even more unique. A delishous and quick falafel sandwich, tasty taboubleh, appetizing ouzi, filling kibbeh, etc. are all apart of Via della Seta's alla carte options that will not leave you by any means unhappy.

Samer Hareb essentially took the same path as Kouki, beginning in Hallak's workshop and going independent. In 2000 he opened his own rug shop, which also sold glassware through the collaboration with his brother living in Damascus, in the artisan street of Via Panico. In the summer of 2014, effectively altering in direction, Hareb opened Via della Seta on Via dei Coronari. From the decoration, the café speaks Old Damascus. In fact, every detail is a reminder of Hareb’s past. Being a proud Damascene from Bab Al Jabeih, Hareb does not leave a moment to remind passer-bys that he is from the oldest inhabited city in the world and personally makes everything on his menu alla Damascena. With the exception of the hand-made kibbeh from a Syrian woman’s kitchen, Hareb wakes up every morning to make his menu ‘fresh’. The quality and distinction of Via della Seta is that the Damascus cuisine is authentically prepared by a Shami, a rare match in itself. Even in Damascus a Damascene is rare, so finding one in Rome cooking food is even more unique. A delishous and quick falafel sandwich, tasty taboubleh, appetizing ouzi, filling kibbeh, etc. are all apart of Via della Seta's alla carte options that will not leave you by any means unhappy.

Grandson of the artist Abu Subhi Al Tinawi, a Damascene artist whose works are even exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum, Hareb demonstrates his family tree in the hangings of the painted glass artworks of the well-known Abla ou Antar stories. Unlike Hallak and Kouki who continue to rely on Eastern accessories, Hareb intends to continue offering Damascene hospitality and cuisine to his customers, both local and international.

Grandson of the artist Abu Subhi Al Tinawi, a Damascene artist whose works are even exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum, Hareb demonstrates his family tree in the hangings of the painted glass artworks of the well-known Abla ou Antar stories. Unlike Hallak and Kouki who continue to rely on Eastern accessories, Hareb intends to continue offering Damascene hospitality and cuisine to his customers, both local and international.

The uniqueness of these Syrian immigrants is their ability to recreate their past in a new continent. Though they have unquestionably integrated well into the city they now call home for over the past two decades, they remain faithful and proud of their origins, always finding new ways to bring Syria to Rome and to its tourists. As their stores and business adjust to the economic changes of the local market, they have not lost their Syrian touch of hospitality, always offering tea and chit-chat to clients, showing customer recognition, even to the little spenders, and continuously yelling out ‘ciao habibi’ to the locals and neighbours passing by the store-front.

Sciam Cafe

Via del Pellegrino, 5500186, Rome

Tel/Fax: +39-6-68308957

Cell.: +39-3337333817

www.facebook.com/pages/Sciam

Kouki

Via dei Coronari, 21300186, Rome

Tel: +39-6-6896704

Mobile: +39-3403530499

www.caucasianrug.com

La Via Della Seta

Via dei Coronari, 143Tel: +39-6-68307438

Cell: +39-3356588553

www.facebook.com/viadellasetaroma

Image Sources:

On-site: November 2014 by S. Sultagi

www.tripadvisor.com

www.tripadvisor.com